The Disaster Era

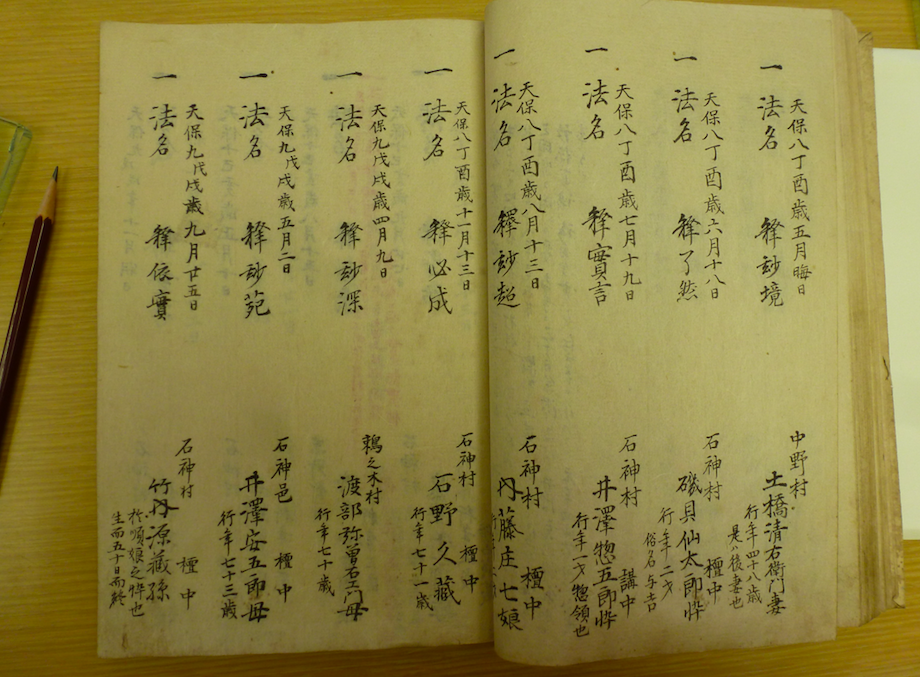

The Rinsenji death register in 1837-38, the aftermath of the Tenpo Famine. Yasugoro’s mother is second from the left.

In November 2016, I knew who I was and what I was doing. I had a two-year-old, a six-year-old, and an aging, floppy-eared mutt. My husband and I paid bills and entered events into our calendar; we scheduled appointments and poured cups of milk and faxed forms that shouldn’t have needed to be faxed. I had all the numbers in my phone and the lists in my head. I had a name for every bunny in our yard. I could find the words to rebuild a lost city and populate it with ghosts. But overnight I realized that none of that mattered: I couldn’t decide the election.

I had always understood, intellectually, that my world was small. I knew it was possible to be overwhelmed by historical forces I didn’t understand. But when the election happened, my attention had been turned in the opposite direction, toward my own domestic realm, where I was supposed to assess and mitigate every risk. Suddenly, I was unable to reconcile the vastness of my responsibilities – which included, as a citizen, the election – and the very limited extent of my power. Many of us who had been privileged enough to enjoy the illusion of control, who spent the months and years after the election thinking about how we could have done more, or tried something different, felt the same way.

In my work, I thought a lot about power, but on a very small scale. I wrote about who spent the money and who scrubbed the floor. My book’s protagonist, Tsuneno, tried to seize control of her own life; she rejected her father’s and brothers’ choices and made her own. But in the aftermath of the election, I thought more about the people on the edges of her story, who seemed less assertive, maybe more ordinary.

I considered a man named Yasugoro, a native of Ishigami village, the author of two very awkwardly written letters in Tsuneno’s family’s archive. He was well-educated for a peasant, but his characters were blocky, his orthography was unconventional, and his meanings were difficult to follow. I tried to piece together a life for him out of the scattered mentions in registers and other people’s letters. I wrote a tiny biography:

“Yasugoro was a peasant from Ishigami Village in Echigo province. He must have been married; he lost two young children in the same terrible year, 1822. His two daughters, Saku and Mayo, died in 1849 at the ages of thirteen and twenty-one. Yasugoro was a devoted patron of his village temple. He was invited to weddings and sent appropriate gifts when he couldn't attend. He worked some winters in the city of Edo, but he always came home. He had terrible handwriting and could barely write a coherent letter, but he was a faithful correspondent. He lent his neighbor a few coins when she got herself in trouble in Edo. He died in the eleventh month of 1853.”

But what could I make out of that life? He was no one’s idea of a progatonist. Not even mine.

Thinking about Yasugoro made me realize that I’ve never had a good answer to my central question: how to measure the smallness of an ordinary life against the terrifying immensity of history. It’s easier when the person in question was clearly a rebel, when, to put in terms of historical jargon, she “had agency.” Then you can establish a classic narrative conflict: an individual against society. But what about the others, the ones who are overwhelmed, carried along, complicit or victimized, or both?

I’m not a historian of the Holocaust, slavery, indigenous dispossession, or war; my scholarship doesn’t tend to explore the limits of what a human being can endure. My subjects’ lives were more difficult than I can fathom, but in some ways the shape of their experience is still familiar. When I thought about the ordinary people who populated my work, I could see myself in the choices they made. My students would ask whether the subjects of the work we read “had agency,” and I would be frustrated. “Do you have agency?” I would ask.

It isn’t that we look for our modern, liberated selves in our historical actors, I would say. It’s that we misunderstand who we are and what our seemingly infinite choices add up to. We focus on individual effort because it’s easier than acknowledging our collective failure, and because it’s paralyzing to realize we don’t know if anything we can do will make a difference. Now, in the midst of disaster, we obsess over our personal choices – don’t go out, wear a mask, wear the mask correctly, wipe down every package, educate the children, make sure you exercise, don’t buy too much, don’t prepare too little – and avoid the hard truth that very little is in our control.

I’m not sure whether the people I study, who lived in Japan two hundred years ago, thought about choice in the same way. But it’s wrong to assume that they were resigned to disaster, believing it was karma. During the catastrophe of the Tenpo Famine, four straight years of failed harvests and epidemics in the late 1830s, priests turned to the language of faith to explain their plight: “The suffering of ordinary people makes me think of the impermanence of this world,” one wrote. “My only hope is to pray for salvation in the next life.” But village headmen, facing impending doom, pleaded for help from their overlords in a tone that reminds me of today’s governors. They understood that the natural disaster was partially manmade, that a different policy might help. The headman in one village in Echigo composed a thorough account of the entire crisis so that people would understand what had happened. He wrote that he wanted people to be prepared so that it could never happen again.

Social historians like to match effects to events, to describe the consequences of failure. We look to mass movements, to rebellions, to numbers and ratios – almost always aggregates, usually involving hundreds if not thousands or even millions of people. Abandoned fields and deaths are (relatively) easy to count. And we know why rioters smashed rice shops and why rebels took up arms. When the samurai Oshio Heihachiro started an uprising in 1837, he wrote a manifesto. His signs read “Save the People.” He wasn’t subtle. If the scale is large enough, or the actors are dramatic and eloquent enough, it isn’t difficult to understand how disaster leads to unrest. It’s a useful kind of story. It enables us to imagine, now, how this catastrophe might give birth to much-needed change.

But what about ordinary people, individuals? In the Tenpo Famine, hundreds of thousands died, but many more survived. What about them? Did they make different choices in the aftermath?

Most of the people I study were fortunate, literate, and wealthy. They survived and wrote very little about the suffering of their neighbors. Maybe they were entirely self-involved, but it’s more likely that they didn’t see the need to keep a record. But as a result, it’s difficult to perceive how the famine shaped their lives, and then it’s mostly guesswork. Did economic stress cause a marriage to fail, or did the couple just not get along? Did the patriarch die of an epidemic disease, or was it something else?

And what I really want to know is even more inaccessible. What changed in their interior lives? Did they make different marriages, go new places, forge new friendships?

Yasugoro survived the famine. He welcomed a new baby, Mayo, at the height of the crisis, and lost his mother two years later. He still went to Edo; he continued to work as a servant in the winters. I don’t know what, if anything, changed for him. But two years after the famine, Tsuneno met a man who made her a proposition. Run away with me, he said. Abandon your village, lie to your family, and pawn your clothes. We’ll leave tomorrow. And given the option, she decided to go.

I can’t connect her decision to the catastrophe of the famine, as much as I would like to. When I look to her neighbors and relatives, more conventional people, I can’t say how the disaster reverberated years and decades later, sending ripples of change into the quiet of everyday life. Some shifts are so subtle that even the people involved in them can’t trace their origin. Some historical phenomena are just too small to see.

I sit in the orange chair in my children’s playroom, surrounded by scattered baseball cards and chess pieces, safe for now. I send messages to my college roommate group chat. Long ago, my friend, also a writer, gave it a jokey title: “Strong Female Protagonists.” Right now it’s hard to believe. I open a new window and email a colleague. “Maybe someday someone will find this correspondence and write a thesis about us,” I write, half seriously. “The minor intellectuals of the disaster era.”

I like to imagine that hypothetical historian, somewhere far away, a native speaker of a different language, puzzling through the English in my emails. I wonder what she will decide about me, sitting in my house, scrolling through Twitter, writing about two hundred year old problems, watching the catastrophe unfold.